From Statue to Status

In the past month, the concept of preservation and transformation of colonialist public monuments has been thoroughly discussed. Always written by the victorious party, the making of History, has been a strategy of power positioning and of the transmission and imposition of inherited power structures. From a written document, to a public monument and then to History books, through several materializations, a chosen side of History becomes officialized, achieving the illusion of impartiality and of unquestionable truth. From Statue to Status, the materialization of historical characters and events allow the possibility of becoming hegemonic and permanent.

Nevertheless, History is a complex living process in constant mutation. A non-linear superposition of events, taking place simultaneously in diverse frames of time and space – all intertwined and interrelated. What it’s commonly understood as History, is only one frame of these realities: it is singular and with capital H. How can we acknowledge the events taking place at the margins? We might refer to them as histories with lower h and in plural.

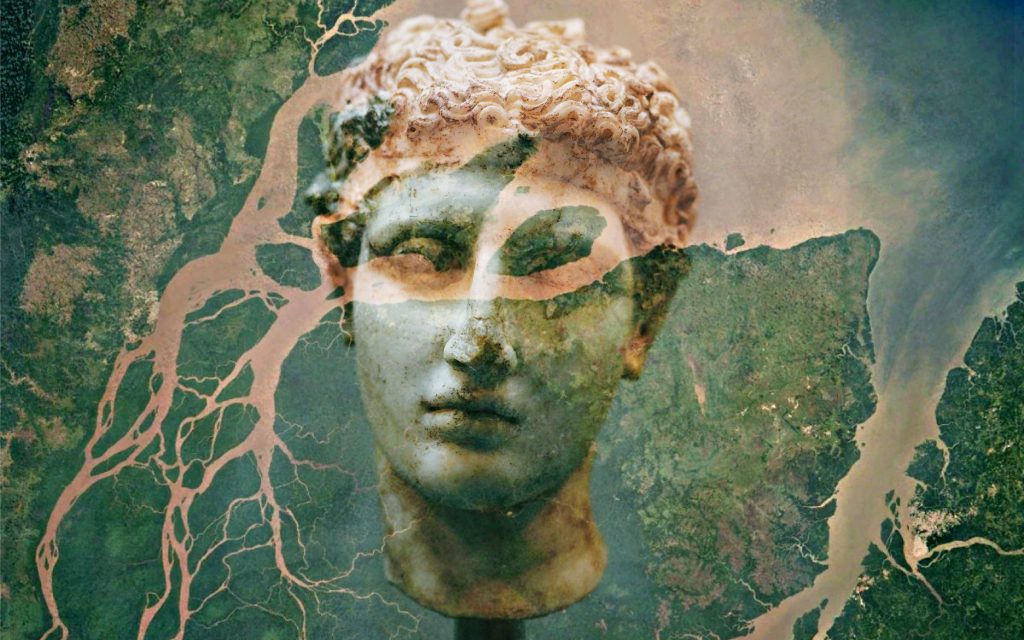

From Ancient Egypt and Greece, several cultures have been built upon projects of immortality, symbolic notions which have often taken the shape of statues. Built over pedestals and very often monumental-oversized; these representations have ultimately elevated a verticality of heroes, anthropomorphic gods above the rest of the planet. Humans above nature, some humans above other humans –– one official History above others. When we relate to our environments from vertical positions, we relate in exploitative ways. The chain reaction of torn down statues, reinterpreted and defied, could have only taken place through the Black Lives Matter movement – an evidence that still in 2020 some lives matter more than others and some histories still remain at the margins.

In a similar process to historization, heroization often standardizes and reduces the complexities of the human character. Certainly, there have been memorable human beings whose actions serve as guiding references, but in order to be more precise, shouldn’t we take actions and not people as references? The materialization of History and heroes as marble bronze, copper or iron statues – hard, resistant and strong materials, negate most possibilities of mutation; in fact, they are made to resist snow storms, rain falls and protests. What if statues and monuments were left to host life in the form of moss, decomposition and bacteria? What if they become living platforms that challenge the concrete?

Grass-root histories

As we begin to understand that we urgently need and can play a more active role in the shaping of histories, a down-to-earth approach to democracy might start to emerge. From the decisions that depicts what occupies our public space and therefore receive our public funds, to the values we praise as a society, and how our alternate histories become perceptible, the exercise of collective examination of how we, as individuals and as a collectivity, have also been complicit in the preservation of certain ideals and action is not only important but urgent.

Coming from Colombia, a country where its own name – the land of Columbus – is an affirmation of its colonial past and a possible obstacle to postcolonial futures, in my school I was taught mainly European colonial History. Within our scarce culture of memory, often insensitive to death, it is only until recently that we conceive the power of citizenship in the construction of our histories. This is why I highly admire the collective public manifestations of acknowledgment of the life and struggle of social leaders and environmentalist activists who have been systematically murdered. I am also quite curious on what can emerge from the recent discussions about potential new name proposals for the country.

From statues that have been replaced with other statues as in Buenos Aires, to that sunk in the ocean as in Bristol , or the one beheaded in Boston, covered by mirrors or plastic bags, left only with a horse, or merely covered with paint, these exercises of collective iconoclastism has evidenced how outdated History is.

Are these manifestations flattening the curve of vertical power? Beyond isolated events, or circumstantial reactions, perhaps we should understand them within broader historical constructions capable of transcending the symbolic realm. Every case is different and should be thoroughly reviewed taking into account its own specificities. In fact, I consider the diversity of approaches necessary in the emergence of plural histories.

Maybe these collective performative examinations could take place periodically over time.

The Great Mosque at Djenné, Mali is being collectively restored every year. “The residents of Djenné come together to put a new layer of clay on their mosque every April, just before the rainy season. The crépissage is both a necessary maintenance task to prevent the mosque’s walls from crumbling and an elaborate festival that celebrates Djenné’s heritage, faith, and community. It’s also an act of defiance.” – I imagine these processes of periodical collective examination, re-shaping and alteration translated into the construction of other symbols and histories.

Non-Anthropomorphic Monuments

So what could we potentially have in the place of outdated statues?

What if pedestals become platforms of speech and public expression where diverse people can stand up and express their opinion? What about update-able monuments made through materials that allow recontextualization? Or digital open source platforms, as Wikipedia, where through a process of consent, users can access and update the content exposed? There are certainly many interesting possibilities we should start considering as a follow up of these actions.

Why have societies chosen to immortalize characters and structures of power who have triggered death? As we are activating our role as citizens in the administration of historical memory, maybe we can also engage ourselves as living beings in the process of administration of the planet. Maybe we begin to conceive horizontal non anthropocentric monuments – altars to praise the life in both humans and non humans.

What if the Amazon rainforest or the Kilimanjaro volcano become our monuments of the future?